A tension pneumothorax represents one of the most life-threatening respiratory emergencies that healthcare providers can encounter. For respiratory therapists, understanding this condition is not merely academic—it’s a clinical imperative that can mean the difference between life and death for patients under their care.

This guide explores the pathophysiology, recognition, and management of a tension pneumothorax, with particular emphasis on its relevance to respiratory care practice.

What is a Tension Pneumothorax?

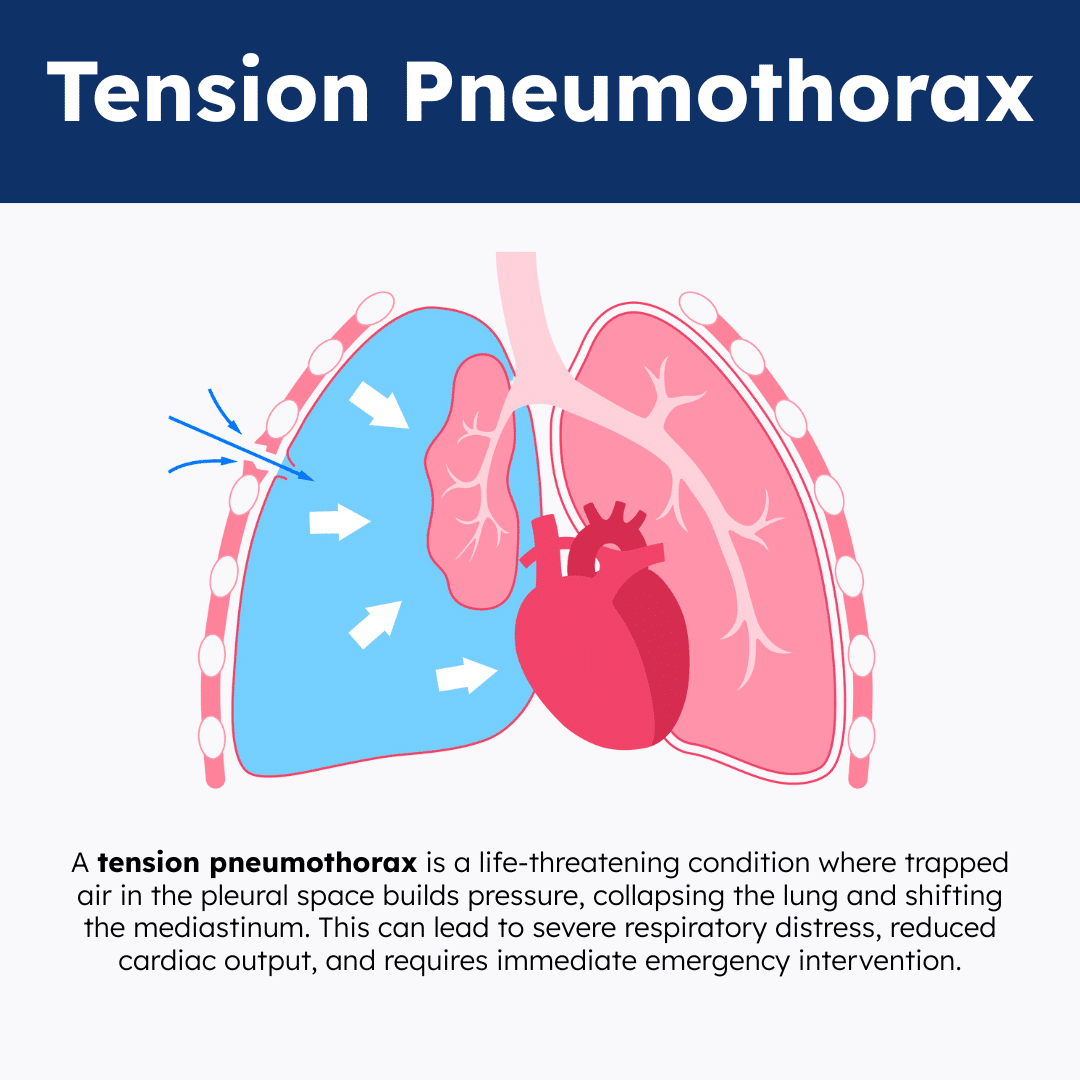

A tension pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space but cannot escape, creating a one-way valve mechanism. Unlike a simple pneumothorax, where air leakage may stabilize or resolve spontaneously, a tension pneumothorax involves progressive air accumulation that leads to increasing intrapleural pressure. This mounting pressure causes compression of the affected lung, mediastinal shift away from the affected side, and ultimately cardiovascular collapse.

The pathophysiology follows a predictable cascade. Initially, air enters the pleural space through a defect in either the visceral pleura (lung surface) or parietal pleura (chest wall).

In a tension pneumothorax, this defect acts as a one-way valve—air enters during inspiration when pleural pressure decreases, but the defect closes during expiration, preventing air from escaping. With each breath, more air accumulates, progressively increasing intrapleural pressure.

Clinical Presentation and Recognition

A tension pneumothorax presents with a constellation of findings that respiratory therapists must recognize immediately. The classic triad includes severe dyspnea, chest pain, and hemodynamic instability. However, the presentation can be subtle initially, particularly in mechanically ventilated patients, where the usual subjective symptoms may be masked.

Respiratory symptoms typically include severe dyspnea, tachypnea, and decreased oxygen saturation despite the use of supplemental oxygen. Patients often exhibit accessory muscle use and may appear cyanotic. Chest pain, when present, is usually sharp and pleuritic, often radiating to the shoulder on the affected side.

Physical examination reveals several key findings. Inspection may show asymmetric chest expansion, with the affected side appearing hyperexpanded. Tracheal deviation away from the affected side is a classic but late finding that indicates significant mediastinal shift. Percussion reveals hyperresonance over the affected side, while auscultation demonstrates absent or markedly diminished breath sounds.

Hemodynamic Manifestations

The hemodynamic presentation of a tension pneumothorax is particularly relevant to respiratory therapists working in critical care settings. Early signs include tachycardia and mild hypotension, which may be attributed to other causes. As the condition progresses, patients develop more severe hypotension, elevated central venous pressure (if monitored), and signs of inadequate tissue perfusion.

Jugular venous distension is common, though it may be difficult to assess in mechanically ventilated patients. Pulse pressure often narrows, and patients may develop pulsus paradoxus—an exaggerated decrease in systolic blood pressure during inspiration.

Etiology and Risk Factors

For respiratory therapists, understanding the iatrogenic causes of a tension pneumothorax is crucial because many procedures within their scope of practice carry this risk. Central venous catheter insertion, particularly subclavian approaches, carries a significant risk of pleural injury. Mechanical ventilation, especially with high pressures or in patients with underlying lung disease, can cause barotrauma, leading to a pneumothorax.

Thoracentesis, chest tube insertion, and percutaneous lung biopsy are additional procedures that can result in tension pneumothorax. Even routine procedures like bag-mask ventilation with excessive pressures can cause pneumothorax in vulnerable patients.

Spontaneous Causes

A spontaneous tension pneumothorax can occur in patients with underlying lung disease or in apparently healthy individuals. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax typically affects tall, thin young men and often occurs without obvious precipitating factors.

A secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in patients with underlying lung disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, pneumonia, or interstitial lung disease.

Traumatic Causes

Blunt or penetrating chest trauma can cause a tension pneumothorax through direct pleural injury or secondary to rib fractures that puncture the lung. Respiratory therapists working in emergency departments or trauma centers must maintain a high suspicion for this complication in trauma patients.

Diagnostic Considerations

A tension pneumothorax is primarily a clinical diagnosis that requires immediate action. In the acute setting, waiting for radiographic confirmation can be fatal. The diagnosis should be suspected in any patient with acute respiratory distress, particularly those with risk factors or a history of recent procedures.

The combination of respiratory distress, hemodynamic instability, and classic physical findings should prompt immediate decompression. In mechanically ventilated patients, sudden increases in peak airway pressures, decreased tidal volumes, or difficulty ventilating may be the first signs.

Imaging Studies

When time permits and the patient is stable, chest X-rays can confirm the diagnosis and assess the degree of lung collapse. However, chest X-rays may be normal in early tension pneumothorax or may underestimate the severity. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is more sensitive but is rarely indicated in the acute setting.

Point-of-care ultrasound has emerged as a valuable tool for rapid diagnosis and treatment. The absence of lung sliding and the presence of a lung point can help confirm pneumothorax, though these findings require proper training to interpret accurately.

Management and Treatment

The primary treatment for a tension pneumothorax is immediate decompression. This can be accomplished through needle decompression or chest tube insertion. Needle decompression is typically performed first as a temporizing measure, using a large-bore needle (14-gauge or larger) inserted in the second intercostal space at the midclavicular line on the affected side.

Note: The goal of needle decompression is to convert a tension pneumothorax into a simple pneumothorax, thereby buying time for definitive treatment. A rush of air upon needle insertion confirms the diagnosis and provides immediate relief of tension.

Definitive Treatment

Definitive treatment typically requires chest tube insertion, which is placed in the fourth or fifth intercostal space at the anterior axillary line. The chest tube allows continuous drainage of air and monitors for ongoing air leaks. Proper chest tube management, including ensuring adequate suction and monitoring for complications, is within the expertise of respiratory therapists.

Special Considerations for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Mechanically ventilated patients present unique challenges in managing a tension pneumothorax. Positive pressure ventilation can worsen the condition by forcing more air into the pleural space. Respiratory therapists must be prepared to manually ventilate with lower pressures or temporarily disconnect the ventilator if necessary during emergency procedures.

Relevance to Respiratory Care Practice

Prevention of a tension pneumothorax is a key responsibility for respiratory therapists. This includes proper ventilator management, avoiding excessive airway pressures, and maintaining vigilance during high-risk procedures. Understanding patient risk factors and implementing appropriate monitoring can help prevent this complication.

Early Recognition and Response

Respiratory therapists are often the first healthcare providers to recognize signs of a tension pneumothorax, particularly in patients who are mechanically ventilated. Changes in ventilator parameters, patient appearance, or hemodynamic status should prompt immediate assessment and, if necessary, emergent intervention.

Collaborative Care

Managing a tension pneumothorax requires a coordinated team approach. Respiratory therapists must communicate effectively with physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to ensure rapid diagnosis and treatment. Understanding each team member’s role and maintaining clear communication channels is essential for optimal patient outcomes.

Education and Training

Respiratory therapists have a responsibility to maintain current knowledge about a tension pneumothorax and to participate in ongoing education and simulation training. This includes staying updated on the latest guidelines, practicing emergency procedures, and mentoring junior staff members.

Complications and Prognosis

Complications of a tension pneumothorax can be severe and life-threatening. Cardiopulmonary arrest is the most feared complication, resulting from severe hypoxemia and cardiovascular collapse. Other acute complications include pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, and injury to surrounding structures during emergency procedures.

Long-term Outcomes

With prompt recognition and appropriate treatment, the prognosis for a tension pneumothorax is generally good. However, delays in diagnosis or treatment can result in significant morbidity or mortality. Some patients may experience recurrent pneumothorax, particularly those with underlying lung disease or structural abnormalities.

Tension Pneumothorax Practice Questions

1. What is a tension pneumothorax?

A life-threatening condition where air enters the pleural space but cannot escape, leading to increased intrathoracic pressure and compression of the lungs and heart.

2. What is the primary pathophysiological feature of a tension pneumothorax?

Air becomes trapped in the pleural space, creating positive pressure that collapses the lung and can shift the mediastinum.

3. What are the classic signs and symptoms of a tension pneumothorax? (TTRAPPED)

Tachycardia, Tracheal deviation, Respiratory distress, Acute hypotension, Pleuritic chest pain, Presence of absent breath sounds unilaterally, Elevated cough, Distended neck veins.

4. What is the initial emergency intervention for a suspected tension pneumothorax?

Immediate needle decompression.

5. Where should a needle be inserted for decompression of a tension pneumothorax?

In the second intercostal space at the midclavicular line, using a large-bore needle.

6. What is the goal of emergent needle decompression in tension pneumothorax?

To relieve trapped air and convert the tension pneumothorax into a simple pneumothorax.

7. After needle decompression, what is the definitive treatment for a tension pneumothorax?

Chest tube insertion to continuously evacuate air from the pleural space.

8. How does a tension pneumothorax affect cardiac output?

It compresses great vessels, reducing venous return to the heart and leading to decreased cardiac output.

9. What physical assessment findings suggest a tension pneumothorax?

Absent breath sounds on the affected side, tracheal deviation away from the affected side, respiratory distress, and distended neck veins.

10. What causes tracheal deviation in tension pneumothorax?

Mediastinal shift caused by increased intrathoracic pressure on the affected side.

11. What are the symptoms of decreased cardiac output in tension pneumothorax?

Hypotension, tachycardia, and signs of shock.

12. What causes distended neck veins in tension pneumothorax?

Compression of the superior vena cava impairs venous drainage from the head and neck.

13. What is the appropriate out-of-hospital dressing technique after decompression?

Apply an occlusive dressing taped on three sides to create a flutter valve effect.

14. What is the recommended oxygen therapy for a tension pneumothorax patient?

100% high-flow oxygen.

15. What are the common traumatic causes of a tension pneumothorax?

Penetrating chest injuries such as stab wounds, gunshot wounds, or blunt trauma from car accidents.

16. What are the major risk factors for developing a tension pneumothorax?

Smoking, genetic predisposition, history of pneumothorax, and mechanical ventilation.

17. What are the common clinical manifestations of a tension pneumothorax?

Ipsilateral chest pain, chest asymmetry, hyperresonant percussion, diminished breath sounds, and tracheal deviation.

18. What is the underlying mechanism of a tension pneumothorax?

Air enters the pleural space but cannot exit, functioning like a one-way valve that builds pressure with each breath.

19. What are the key physical findings that help identify a tension pneumothorax?

Jugular vein distention, tracheal deviation, and signs of mediastinal shift.

20. What serious complication can result from untreated tension pneumothorax?

Obstructive shock due to reduced cardiac output and vascular collapse.

21. What should you do if you suspect a tension pneumothorax in a prehospital setting?

Request advanced life support (ALS) and prepare for rapid transport (“load and go”).

22. Who is authorized to perform emergency needle decompression in the field?

Only trained ALS providers (such as paramedics or physicians).

23. What are the early warning signs of a developing tension pneumothorax?

Absent breath sounds, restlessness, and narrowing pulse pressure.

24. What symptoms are typically seen during the intermediate stage of a tension pneumothorax?

Cyanosis and increasing cardiovascular instability.

25. What characterizes the late stage of tension pneumothorax?

Severe hemodynamic compromise, marked tracheal deviation, cardiac compression, and vascular collapse.

26. What happens when air accumulates between the lung and chest wall, increasing intrathoracic pressure and reducing venous return?

Tension pneumothorax occurs, potentially leading to cardiovascular collapse.

27. A patient presents with a chest wound, dyspnea, and a “sucking” sound during breathing. Breath sounds are absent on the affected side, and the chest X-ray shows a pneumothorax. What type is most likely?

Open pneumothorax

28. What is considered a late clinical sign of a developing tension pneumothorax?

Tracheal deviation

29. While assessing a patient with a pneumothorax, you observe swollen, crackling areas under the skin on the face, neck, and chest. What is this finding called?

Subcutaneous emphysema

30. You are caring for a patient with a chest tube. There is no fluctuation in the water seal chamber and no kinks in the tubing. What is your next step?

Assess the patient’s lung sounds to determine if the lung has re-expanded.

31. A patient on mechanical ventilation with PEEP develops hypotension, tachypnea, tracheal deviation, and jugular venous distention. What condition is most likely?

Tension pneumothorax

32. A patient with a chest tube for a left-sided pneumothorax has developed a slight tracheal deviation to the right. What should you do?

Immediately notify the provider—this may indicate a tension pneumothorax.

33. What is a true statement about tension pneumothorax?

It is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate needle decompression.

34. A patient’s chest drainage system is cracked and leaking. What is your immediate priority action?

Submerge the chest tube 1 inch into sterile water and replace the drainage system.

35. What are the three main types of pneumothorax?

Spontaneous, open, and closed pneumothorax

36. What occurs in a primary spontaneous pneumothorax?

Small blebs on the lung surface rupture, releasing air into the pleural space without trauma.

37. What occurs in an open pneumothorax?

Air enters the pleural space through an open wound in the chest wall, often producing a sucking sound during breathing.

38. What occurs in a closed pneumothorax?

Air enters the pleural space without external trauma, often due to a fractured rib puncturing the lung.

39. What is the definition of a pneumothorax?

The presence of air in the pleural space, either from within the lungs or from the external environment.

40. What defines a primary spontaneous pneumothorax?

It occurs in individuals without pre-existing lung disease.

41. What defines a secondary spontaneous pneumothorax?

It occurs in patients with underlying lung disease, such as COPD or cystic fibrosis.

42. What is the mechanism of a tension pneumothorax?

Air accumulates in the pleural space under pressure, collapsing the lung and shifting the mediastinum, impairing venous return.

43. Why is a tension pneumothorax considered life-threatening?

It compresses the heart and vena cava, reducing cardiac output and leading to shock.

44. What is a serious complication that can arise from any type of pneumothorax?

Progression to tension pneumothorax

45. What is a hemothorax?

A condition where blood accumulates in the pleural space.

46. What is the treatment of choice for a hemothorax?

Insertion of a chest tube to drain the blood.

47. What symptoms are commonly associated with a hemothorax?

Chest pain, bruising, shortness of breath, and decreased breath sounds on the affected side.

48. What are the common causes of a traumatic open pneumothorax?

Penetrating chest injuries, such as stab or gunshot wounds.

49. What condition presents with hyperresonance on percussion and diminished breath sounds?

Pneumothorax

50. What is the primary diagnostic tool used to confirm a pneumothorax?

Chest X-ray

51. What is the immediate danger of air trapping in a tension pneumothorax?

It increases intrathoracic pressure, collapsing the lung and shifting the mediastinum.

52. What chest tube finding indicates the lung may have fully re-expanded?

No fluctuation in the water seal chamber during breathing.

53. What nursing intervention prevents air from re-entering the pleural space after a chest tube becomes disconnected?

Submerge the tube in sterile water to create a temporary seal.

54. What finding most reliably confirms the diagnosis of tension pneumothorax over simple pneumothorax?

Tracheal deviation and cardiovascular compromise

55. What role does smoking play in the development of spontaneous pneumothorax?

It increases the risk by damaging alveoli and promoting bleb formation.

56. What is the recommended emergency treatment for an open pneumothorax?

Application of a chest seal (e.g., Russell’s chest seal) that prevents air from entering the pleural space during inhalation while allowing air and blood to escape during exhalation.

57. What is the appropriate treatment for a closed pneumothorax showing signs of decompensation?

Perform needle decompression to relieve pressure in the pleural space.

58. According to NICE guidelines, when should needle decompression be performed in a patient with pneumothorax?

When the patient shows signs of hemodynamic instability or severe respiratory compromise.

59. Where should a needle decompression be performed, and how is it done?

Insert a large-bore cannula into the 2nd intercostal space at the midclavicular line; if no improvement, a 14G cannula can be inserted in the 5th intercostal space anterior to the mid-axillary line.

60. What is the next step if a second needle decompression fails to relieve a tension pneumothorax?

A specialist should perform an open thoracotomy followed by chest tube insertion.

61. What are the components of initial treatment for a tension pneumothorax?

Needle decompression, high-flow oxygen, effective analgesia, IV access, and administration of IV antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav 1.2 g.

62. Why is prehospital drainage not recommended for a hemothorax?

Due to a high risk of complications, according to TARN (Trauma Audit and Research Network) guidelines.

63. What are the key principles of treating hemothorax in the prehospital setting?

Minimal patient movement, administration of tranexamic acid (TXA), and fluid resuscitation with permissive hypotension targeting a systolic BP of 90 mmHg.

64. What are the classic symptoms of a pneumothorax?

Tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnea, hypoxia, jugular vein distension, tracheal deviation, chest pain, hyperresonance, and decreased breath sounds on the affected side.

65. What clinical finding is characteristic of an open pneumothorax?

A visible chest wound producing a sucking sound and bubbling during respiration.

66. What are the typical signs of a hemothorax?

Hypotension, tachypnea, reduced breath sounds on the affected side, hemoptysis, and dullness to percussion.

67. If untreated, what can a pneumothorax ultimately lead to?

Cardiopulmonary collapse and severe hypoxia.

68. What is the pathophysiology behind a tension pneumothorax?

Air enters the pleural space and becomes trapped, causing increased pressure that collapses the lung and shifts the mediastinum to the opposite side.

69. What are the common causes of a tension pneumothorax?

Mechanical ventilation (barotrauma), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and traumatic chest injury.

70. What clinical feature of tension pneumothorax impairs cardiac filling?

Compression of the great veins leads to hypotension due to reduced venous return.

71. On physical exam, what sign strongly indicates a tension pneumothorax?

Tracheal deviation away from the affected side.

72. What are the five key clinical signs of a tension pneumothorax?

Hypotension, distended neck veins, tracheal shift, absent breath sounds on the affected side, and hyperresonance to percussion.

73. Why is tension pneumothorax considered a medical emergency?

It can lead to hemodynamic collapse due to decreased cardiac output and hypoxemia.

74. What is the immediate treatment for a suspected tension pneumothorax?

Chest decompression with a large-bore needle in the 2nd or 3rd intercostal space at the midclavicular line, followed by chest tube placement.

75. What is the correct initial step if tension pneumothorax is suspected?

Perform immediate needle decompression—do not delay treatment to obtain a chest X-ray.

76. What mechanism makes a tension pneumothorax more dangerous than a simple pneumothorax?

Air enters the pleural space and becomes trapped, progressively increasing intrathoracic pressure and compromising cardiopulmonary function.

77. What is the effect of tension pneumothorax on preload and cardiac output?

Increased pressure compresses the great veins, reducing venous return and leading to decreased cardiac output.

78. In a trauma patient, which clinical triad suggests the development of a tension pneumothorax?

Tracheal deviation, hypotension, and unilateral absence of breath sounds.

79. Why is tracheal deviation a late sign of a tension pneumothorax?

It occurs after significant pressure buildup has shifted the mediastinum to the unaffected side.

80. What finding on percussion is typically present on the affected side in tension pneumothorax?

Hyperresonance due to trapped air in the pleural space.

81. What happens to the unaffected lung during a tension pneumothorax?

It is compressed by the shifting mediastinum, reducing its ability to ventilate.

82. Why does jugular vein distension occur in tension pneumothorax?

Increased intrathoracic pressure impairs venous return to the heart.

83. Which diagnostic tool is most useful in confirming tension pneumothorax if time allows?

Chest X-ray, although treatment should not be delayed to obtain imaging.

84. What does a “sucking” chest wound indicate in the context of tension pneumothorax?

An open pneumothorax may progress to a tension pneumothorax if air cannot escape.

85. What vital sign changes are commonly seen in a patient with tension pneumothorax?

Tachycardia, hypotension, and tachypnea.

86. What immediate action should be taken if a patient with chest trauma becomes rapidly unstable?

Perform emergent needle decompression to relieve intrathoracic pressure.

87. What anatomical location is used for needle decompression to treat a tension pneumothorax?

2nd intercostal space, midclavicular line.

88. How does positive-pressure ventilation contribute to tension pneumothorax?

It can force air into the pleural space, especially in patients with underlying lung injury.

89. Why should you avoid delaying treatment for imaging when tension pneumothorax is suspected?

It is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate decompression to prevent cardiac arrest.

90. What is the function of a chest tube following needle decompression?

It continuously evacuates air and prevents the recurrence of pressure buildup.

91. What might indicate that a chest tube for pneumothorax is no longer functioning properly?

Sudden loss of fluctuation in the water seal chamber and worsening respiratory status.

92. In what types of patients is spontaneous tension pneumothorax more common?

Patients with underlying lung disease or a history of previous pneumothorax.

93. What role does oxygen play in the management of tension pneumothorax?

100% oxygen can help reduce the size of the pneumothorax by speeding up nitrogen reabsorption.

94. What should be done if subcutaneous emphysema is noted after trauma?

Suspect pneumothorax or chest tube malfunction and assess the airway and breathing immediately.

95. What type of breath sounds are typically heard over the affected area in tension pneumothorax?

Absent or markedly diminished breath sounds.

96. Why is it dangerous to perform a logroll on a patient with suspected hemothorax or pneumothorax?

It may dislodge clots or worsen internal bleeding and respiratory compromise.

97. What does dullness to percussion suggest in a trauma patient with respiratory distress?

A possible hemothorax rather than a pneumothorax.

98. What condition may present similarly to tension pneumothorax but involves blood in the pleural cavity?

Hemothorax

99. What is the primary difference between simple and tension pneumothorax?

Tension pneumothorax involves progressive pressure buildup, causing mediastinal shift and cardiovascular compromise.

100. What intervention is contraindicated before decompression when tension pneumothorax is suspected?

Waiting for imaging confirmation before needle decompression.

Final Thoughts

A tension pneumothorax represents a critical emergency that demands immediate recognition and intervention. For respiratory therapists, understanding this condition goes beyond academic knowledge—it’s an essential clinical skill that can save lives. The ability to recognize early signs, understand the pathophysiology, and participate effectively in emergency management makes respiratory therapists invaluable members of the healthcare team.

The key to successful management lies in maintaining a high level of clinical suspicion, particularly in high-risk patients and situations. Early recognition, prompt decompression, and coordinated team care are the cornerstones of effective treatment.

By thoroughly understanding a tension pneumothorax, respiratory therapists can better serve their patients, contribute to positive outcomes, and fulfill their professional responsibility to provide safe and effective care in all clinical situations. The knowledge and skills required to manage this condition exemplify the critical thinking and clinical expertise that define modern respiratory care practice.

Written by:

John Landry is a registered respiratory therapist from Memphis, TN, and has a bachelor's degree in kinesiology. He enjoys using evidence-based research to help others breathe easier and live a healthier life.

References

- Sahota RJ, Sayad E. Tension Pneumothorax. 2024 Jan 30. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.